Claude Abeille is a lucky man: he was born with a gift – being a sculptor, and a name – that of a builder insect, the bee. However, his work does not present a bestiary but a cloakroom (vestiaire). After the revolutions which decapitate, our mediocracy cuts the heads that stand too tall over the line; Claude Abeille was thus quickly aware of an impossibility: depicting the man of the 20th century. So he turned to clothing to reconquer the body, because, contrary to the proverb, the clothes may in fact somewhat shape the man. One just has to look, in Rome, at Bernini’s Saint Theresa in ecstasy, more expressive in the quivering of the marble folds than in the swoon on her face.

The mythical work of the 20th century would be related to another form of ecstasy: Marcel Duchamp’s Le Grand Verre ou La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Large Glassor the Bride stripped by her single men) is often described as a “kind of mechanical wasp displaying its wheels above nine single people in uniform, illustrated by copper molds”. Duchamp asserted he had been inspired by fairground stalls “where mannequins, often representing characters at a wedding, could be decapitated by adroitly hurling balls at them”. As uniforms denoted for him the idea of a single male, he organized a “cemetery of uniforms and domestic clothes”.

Abeille’s cloakroom is a response from sculptor to the conceptualist. Far from taking part in the killing game, Abeille undertakes to returns to Being via its envelope. In the beginning was the fold – only the fold allows him to go from a surface to a volume; the dress of the Sphinx has told us that “the time of men is folded eternity” (1).

Clothes without their users are petrified like old shells. Competition, so valued socially, is like a sack race: Abeille puts on parade on a podium several goatskin bottles full of wind. Here is a man who has many tricks in his marble.

So, here is a forest of sculpted pants where the legs have sometimes the strength of trees trunks, and sometimes the grace of columns: the propylea of a generation which overindulged in wearing blue jeans.

Resistant to its canning, a skull is ready to come out: will it escape ? But the nude loses facein a cloth that bubbles with convolutions as a brain made of fabric.

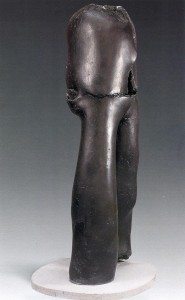

The bronze piece entitled “Strates” (Strata) shows a cleaved bust, with faults where all the geology of the clothing is reaching the surface, wool layer upon cotton layer. But the drill plate is somewhat stiff, and the bust is redolent of a book-man, as described by Ray Bradbury in Fahrenheit 451. In this science-fiction story, books are exterminated by fire, and the firemen themselves performing the autos-da-fé. At the beginning of the 21st century, it is the fire of entertainment that exterminates culture – the culture of books or paintings, and many intellectuals destroy what they should defend. In Bradbury’s work, a few dissidents resisted while learning classics by heart and reciting them. This, the bust in Strates could not do, as the head is missing. It hardly shows on top of a traveller; a head stands out, at last, the head of a man getting on board whose coat pleats in the wind like a flag.

Man, longing for integrity, often appears negatively in Abeille’s work; human flesh fits into clothes, as narrowly as wax and bronze fit together. Cocoons and carcasses of wool, seem, by their transposition into a noble material, to hatch a resurrection. The epic of the sculptor meets the legend of Aristea who unwittingly caused the death of Eurydice, bring desolation to his region. To foster the return of prosperity, he had to sacrifice animals, and understood that his plea had been satisfied when life returned to the bodies … as a swarm of bees Wladimir Weidlé made a book of it, “Les Abeilles d’Aristée” (The Bees of Aristea), which announced the slow Rebirth of art after its modern vicissitudes. From the same myth, Claude Abeille makes sculptures.

Christine Sourgins

art historian.

(1) Anubis, showing the dress of the Sphinx : “Look at the folds of this dress. Press them one against each other. Now, if you drive a pin across this mass and remove it, if you smooth the canvas until removing any trace of the old folds, do think you that even a mere lout can believe that the countless holes repeated across the dress are the result of a single prick of a pin ?” Jean Cocteau, La Machine Infernale, Act II.