Resisting the force which devastates forest and men… with a path of flowers. This is the way chosen by the Kichwa people of Sarayaku. On November 24, 2009, their chief, José Gualinga, had come to Paris to exhibit it in the Krajcberg gallery. A current art lover considers it sees close to land art, and several contemporary artists are willing to defend, with American Indians, their “border of life”. By solidarity? By interest (disorganizing Amazonia is also disturbing our ecosystem…) ? Is the advocacy of a faraway cause the result of a Manichean self-loathing? (hastily going from denouncing the “poison of the Western world” to alleging that “the Western world is itself poisonous”)?… Maybe José Gualinga has come to recall us that this struggle is ours, because it this is already rooted in our own history. The memory of art shows that the border of life goes right inside the Western world.

Thus, the tulip, this flower from Asia, caused in the 17th century, in the Netherlands, a speculative bubble (possibly the first ever): one buys in advance virtual bulbs, one speculates on the fertility of nature, one overworks it (horticulturists rival with pompous names for their creations) and everything collapses… What is art saying at the same time? It resists in its own way, peacefully, and uses the tulip to express vanity. A flourishing genre in the Netherlands depicts glorified flowers –“still life”. The humble lifestyle gently but firmly opposes this spirit of profit, which would pay more for a tulip bulb than for a Rembrandt painting or a house. Art gives those perishable flowers, transformed into banknotes, an access to sustainable development and ethics before these concepts took shape. Some think the tulip craze is the ancestor of the frenzy over subprimes and Madoff’s dealings – the mindset which is devastating the planet today.

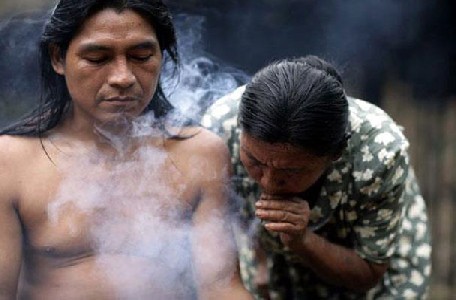

In this alliance between art and flowers, women played their part, including Louise Moillon (1610-1696) and Séraphine (1864-1942). There are many commonalities between this plebeian, provincial woman, and a native. Both are “of humble extraction” (the term is redolent of humus, the nourishing earth). Séraphine paints spontaneously and, as the Kichwa people, uses the floral theme. She is despised. She is an untiring worker, lives frugally, finds inspiration and comfort in trees, plants and animals. She is pious and visionary, is considered as a lunatic (she has designed her own practices and rituals). She concocts an “energy wine”. Her flowers have the vitality of a burning bush, they are mystical… in short, she is somehow a “yachak” (shaman) in her own way. She has been dubbed “the last fairy of our soil”.

Séraphine, although helped by the esthete Wilhelm Uhde, was treated harshly by the good society, recalling the violence against natives. She died of hunger in a psychiatric hospital in 1942. Symbolically, our last fairy dies at the same time as herboristry: the Vichy regime discredited it and suppressed the herbalist diploma. Mother Nature is blamed for not being a market: she offer cheap remedies, in the face of the globalized trade… Yet, painting and medicine have always been associated, and Saint Luke is the patron of painters and doctors. The last of the Mohicans of sorts, herbalist graduate Marie-Antoinette Mulot, died in 1999. In South America one devastates and arsons; in Europe, there is a more discrete way: one asphyxiates and undermines.

Over there they burn their enemies; here they extinguish them… …

Gradual choking is the perspective of the current artists who do not belong to this speculative, de-substantiated art, where it suffices to brand just about anything as “art” to create value, with the same arbitrary power that fixes the price of a banknote. “Financial art”, with its huge biddings, comes straight from the tulip craze… and produces numerous GMOs: “gravely mercantile opuses”. Those artists who are not part of its networks of power and finance are the Indians of the Western world. This is why the struggle of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku is also theirs… the safeguarding of natural diversity goes hand in hand with the concern for cultural diversity.

Christine Sourgins

art historian

Text published in Ecritique review N°10, 1er sem 2010, p. 48 à 57, in homage to the Kichwa people.